Sequence Alignment

Why Do We Align Sequences?

Because similarity reveals relationships.

If two protein or DNA sequences are similar, they likely:

- Share a common ancestor (homology)

- Have similar functions (we can transfer annotations)

- Adopt similar structures (especially for proteins)

The core idea: Evolution preserves what works. Similar sequences suggest shared evolutionary history, which means shared function and structure.

Without alignment, we can't quantify similarity. Alignment gives us a systematic way to compare sequences and measure their relatedness.

Pairwise vs Multiple Sequence Alignment

| Feature | Pairwise Alignment | Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Align two sequences | Align three or more sequences |

| Purpose | Find similarity between two sequences | Find conserved regions across multiple sequences |

| Algorithms | Needleman-Wunsch (global) Smith-Waterman (local) | Progressive (ClustalW, MUSCLE) Iterative (MAFFT) Consistency-based (T-Coffee) |

| Complexity | O(n²) - fast | O(n^k) where k = number of sequences - slow |

| Common Tools | BLAST, FASTA EMBOSS (Needle, Water) | ClustalW, ClustalOmega MUSCLE, MAFFT T-Coffee, Clustal Phi |

| Output | One optimal alignment | Consensus of all sequences |

| Best For | Comparing two proteins/genes Database searches | Phylogenetic analysis Finding conserved motifs Family analysis |

Pairwise Sequence Alignment

The basic scenario in bioinformatics:

- You have a sequence of interest (newly discovered, unknown function)

- You have a known sequence (well-studied, annotated)

- Question: Are they similar?

- Hypothesis: If similar, they might share function/structure

Sequence Identity

Sequence identity is the percentage of exact matches between aligned sequences.

Example:

Seq1: ACGTACGT

Seq2: ACGTCCGT

||||.|||

Identity: 7/8 = 87.5%

But identity alone doesn't tell the whole story - we need to consider biological similarity (similar but not identical amino acids).

Two Types of Sequence Alignment

Global Alignment

Goal: Align every residue in both sequences from start to end.

Residue = individual unit in a sequence:

- For DNA/RNA: nucleotide (A, C, G, T/U)

- For proteins: amino acid

How it works:

- Start sequences at the same position

- Optimize alignment by inserting gaps where needed

- Forces alignment of entire sequences

Example (ASCII):

Seq1: ACGTACGT----

|||| |||

Seq2: ACGTTACGTAGC

Best for: Sequences of similar length that are expected to be similar along their entire length.

Local Alignment

Goal: Find the most similar regions between sequences, ignoring less similar parts.

How it works:

- Identify regions of high similarity

- Ignore dissimilar terminals and regions

- Can find multiple local alignments in the same pair

Example (ASCII):

Seq1: GTACGT

||||||

Seq2: AAAAGTGTACGTCCCC

Only the middle region is aligned; terminals are ignored.

Best for:

- Short sequence vs. longer sequence

- Distantly related sequences

- Finding conserved domains in otherwise divergent proteins

Scoring Alignments

Because there are many possible ways to align two sequences, we need a scoring function to assess alignment quality.

Simple Scoring: Percent Match

Basic approach: Count matches and calculate percentage.

Seq1: ACGTACGT

|||| |||

Seq2: ACGTTCGT

Matches: 7/8 = 87.5%

Problem: This treats all mismatches equally. But some substitutions are more biologically likely than others.

Additive Scoring with Linear Gap Penalty

Better approach: Assign scores to matches, mismatches, and gaps.

Simple scoring scheme:

- Match (SIM): +1

- Mismatch: -1

- Gap penalty (GAP): -1

Formula:

Score = Σ[SIM(s1[pos], s2[pos])] + (gap_positions × GAP)

Example:

Seq1: ACGT-ACGT

|||| ||||

Seq2: ACGTTACGT

Matches: 8 × (+1) = +8

Gap: 1 × (-1) = -1

Total Score = +7

Affine Gap Penalty: A Better Model

Problem with linear gap penalty: Five gaps in one place vs. five gaps in different places - which is more biologically realistic?

Answer: Consecutive gaps (one insertion/deletion event) are more likely than multiple separate events.

Affine gap penalty:

- GOP (Gap Opening Penalty): Cost to START a gap (e.g., -5)

- GEP (Gap Extension Penalty): Cost to EXTEND an existing gap (e.g., -1)

Formula:

Score = Σ[SIM(s1[pos], s2[pos])] + (number_of_gaps × GOP) + (total_gap_length × GEP)

Example:

One gap of length 3: GOP + (3 × GEP) = -5 + (3 × -1) = -8

Three gaps of length 1: 3 × (GOP + GEP) = 3 × (-5 + -1) = -18

Consecutive gaps are penalized less - matches biological reality better.

DNA vs. Protein Level Alignment

The Problem

Consider these DNA sequences:

DNA1: CAC

DNA2: CAT

||.

At the DNA level: C matches C, A matches A, but C doesn't match T (67% identity).

But translate to protein:

CAC → Histidine (His)

CAT → Histidine (His)

Both code for the same amino acid! At the protein level, they're 100% identical.

Which Level to Use?

DNA alignment:

- More sensitive to recent changes

- Can detect synonymous mutations

- Good for closely related sequences

Protein alignment:

- Captures functional conservation

- More robust for distant relationships

- Ignores silent mutations

Rule of thumb: For evolutionary distant sequences, protein alignment is more informative because the genetic code is redundant - multiple codons can encode the same amino acid.

Substitution Matrices: Beyond Simple Scoring

The DNA Problem: Not All Mutations Are Equal

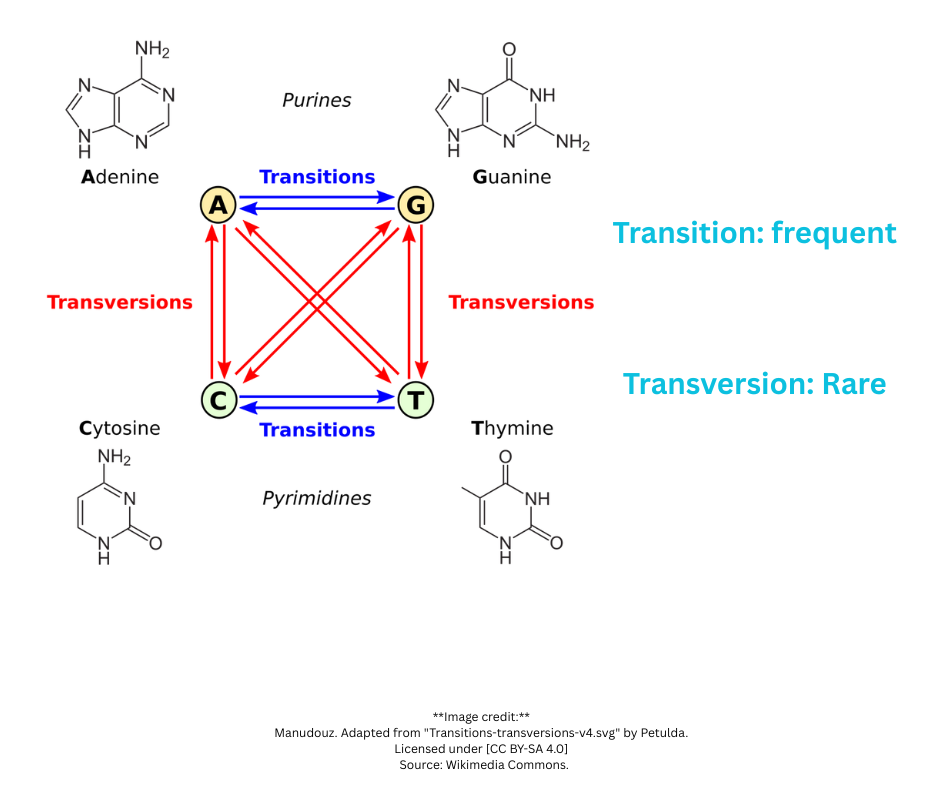

Transitions (purine ↔ purine or pyrimidine ↔ pyrimidine):

- A ↔ G

- C ↔ T

- More common in evolution

Transversions (purine ↔ pyrimidine):

- A/G ↔ C/T

- Less common (different ring structures)

Implication: Not all mismatches should have the same penalty. A transition should be penalized less than a transversion.

The Protein Problem: Chemical Similarity

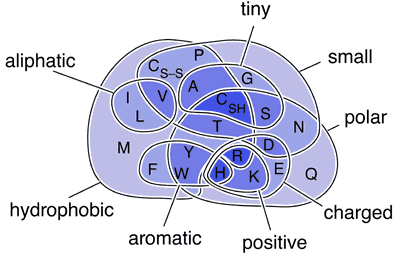

Amino acids have different chemical properties:

- Hydrophobic vs. hydrophilic

- Charged vs. neutral

- Small vs. large

- Aromatic vs. aliphatic

Key insight: Substitutions between chemically similar amino acids (same set in the diagram) occur with higher probability in evolution.

Example:

- Leucine (Leu) → Isoleucine (Ile): Both hydrophobic, similar size → common

- Leucine (Leu) → Aspartic acid (Asp): Hydrophobic → charged → rare

Problem: Venn diagrams aren't computer-friendly. We need numbers.

Solution: Substitution matrices.

PAM Matrices (Point Accepted Mutation)

Image © Anthony S. Serianni. Used under fair use for educational purposes.

Source: https://www3.nd.edu/~aseriann/CHAP7B.html/sld017.htm

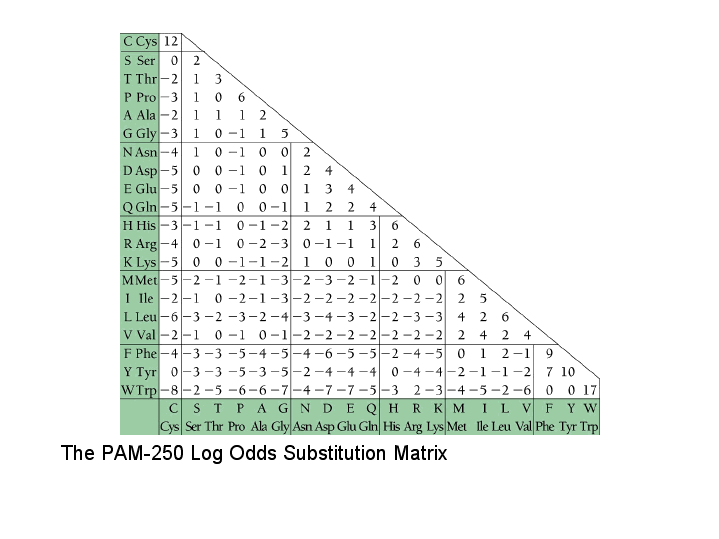

PAM matrices encode the probability of amino acid substitutions.

How to read the matrix:

- This is a symmetric matrix (half shown, diagonal contains self-matches)

- Diagonal values (e.g., Cys-Cys = 12): Score for matching the same amino acid

- Off-diagonal values: Score for substituting one amino acid for another

Examples from PAM250:

- Cys ↔ Cys: +12 (perfect match, high score)

- Pro ↔ Leu: -3 (not very similar, small penalty)

- Pro ↔ Trp: -6 (very different, larger penalty)

Key principle: Similar amino acids (chemically) have higher substitution probabilities and therefore higher scores in the matrix.

What Does PAM250 Mean?

PAM = Point Accepted Mutation

PAM1: 1% of amino acids have been substituted (very similar sequences)

PAM250: Extrapolated to 250 PAMs (very distant sequences)

Higher PAM number = more evolutionary distance = use for distantly related proteins

BLOSUM Matrices (BLOcks SUbstitution Matrix)

BLOSUM is another family of substitution matrices, built differently from PAM.

How BLOSUM is Built

Block database: Collections of ungapped, aligned sequences from related proteins.

Amino acids in the blocks are grouped by chemistry of the side chain (like in the Venn diagram).

Each value in the matrix is calculated by:

Frequency of (amino acid pair in database)

÷

Frequency expected by chance

Then converted to a log-odds score.

Interpreting BLOSUM Scores

Zero score:

Amino acid pair occurs as often as expected by random chance.

Positive score:

Amino acid pair occurs more often than by chance (conserved substitution).

Negative score:

Amino acid pair occurs less often than by chance (rare/unfavorable substitution).

BLOSUM Naming: The Percentage

BLOSUM62: Matrix built from blocks with no more than 62% similarity.

What this means:

- BLOSUM62: Mid-range, general purpose

- BLOSUM80: More related proteins (higher % identity)

- BLOSUM45: Distantly related proteins (lower % identity)

Note: Higher number = MORE similar sequences used to build matrix.

Which BLOSUM to Use?

Depends on how related you think your sequences are:

Comparing two cow proteins?

Use BLOSUM80 (closely related species, expect high similarity)

Comparing human protein to bacteria?

Use BLOSUM45 (distantly related, expect low similarity)

Don't know how related they are?

Use BLOSUM62 (default, works well for most cases)

PAM vs. BLOSUM: Summary

| Feature | PAM | BLOSUM |

|---|---|---|

| Based on | Evolutionary model (extrapolated mutations) | Observed alignments (block database) |

| Numbers mean | Evolutionary distance (PAM units) | % similarity of sequences used |

| Higher number | More distant sequences | More similar sequences (opposite!) |

| PAM250 ≈ | BLOSUM45 | (both for distant proteins) |

| PAM100 ≈ | BLOSUM80 | (both for close proteins) |

| Most common | PAM250 | BLOSUM62 |

Key difference in naming:

- PAM: Higher number = MORE evolutionary distance

- BLOSUM: Higher number = LESS evolutionary distance (MORE similar sequences)

Which to use?

- BLOSUM is more commonly used today (especially BLOSUM62)

- PAM is more theoretically grounded but less practical

- For most purposes: Start with BLOSUM62

Dynamic Programming

Please see the complete topic written in this seperate page