Welcome

Hello, I'm Mahmoud, and these are my notes. Since you're reading something I've written, I want to share a bit about how I approach learning and what you can expect here.

Want to know more about me? Check out my blog at mahmoud.ninja

My Philosophy

I believe there are no shortcuts to success. To me, success means respecting your time, and before investing that time, you need a plan rooted in where you want to go in life.

Learn, learn, learn, and when you think you've learned enough, write it down and share it.

About These Notes

I don't strive for perfectionism. Sometimes I write something and hope someone will point out where I'm wrong so we can both learn from it. That's the beauty of sharing knowledge: it's a two-way street.

I tend to be pretty chill, and I occasionally throw in some sarcasm when it feels appropriate. These are my notes after all, so please don't be annoyed if you encounter something that doesn't resonate with you, just skip ahead.

I'm creating this resource purely out of love for sharing and teaching. Ironically, I'm learning more by organizing and explaining these concepts than I ever did just studying them. Sharing is learning. Imagine if scientists never shared their research, we'd still be in the dark ages.

Licensing & Copyright

Everything I create here is released under Creative Commons (CC BY 4.0). You're free to share, copy, remix, and build upon this material for any purpose, even commercially, as long as you give appropriate credit.

Important Legal Notice

I deeply respect intellectual property rights. I will never share copyrighted materials, proprietary resources, or content that was shared with our class under restricted access. All external resources linked here are publicly available or properly attributed.

If you notice any copyright violations or improperly shared materials, please contact me immediately at mahmoudahmedxyz@gmail.com, and I will remove the content right away and make necessary corrections.

Final Thoughts

I have tremendous respect for everyone in this learning journey. We're all here trying to understand complex topics, and we all learn differently. If these notes help you even a little bit, then this project has served its purpose.

Linux Fundamentals

The History of Linux

In 1880, the French government awarded the Volta Prize to Alexander Graham Bell. Instead of going to the Maldives (kidding...he had work to do), he went to America and opened Bell Labs.

This lab researched electronics and something revolutionary called the mathematical theory of communications. In the 1950s came the transistor revolution. Bell Labs scientists won 10 Nobel Prizes...not too shabby.

But around this time, Russia made the USA nervous by launching the first satellite, Sputnik, in 1957. This had nothing to do with operating systems, it was literally just a satellite beeping in space, but it scared America enough to kickstart the space race.

President Eisenhower responded by creating ARPA (Advanced Research Projects Agency) in 1958, and asked James Killian, MIT's president, to help develop computer technology. This led to Project MAC (Mathematics and Computation) at MIT.

Before Project MAC, using a computer meant bringing a stack of punch cards with your instructions, feeding them into the machine, and waiting. During this time, no one else could use the computer, it was one job at a time.

The big goal of Project MAC was to allow multiple programmers to use the same computer simultaneously, executing different instructions at the same time. This concept was called time-sharing.

MIT and Bell Labs cooperated and developed the first operating system to support time-sharing: CTSS (Compatible Time-Sharing System). They wanted to expand this to larger mainframe computers, so they partnered with General Electric (GE), who manufactured these machines. In 1964, they developed the first real OS with time-sharing support called Multics. It also introduced the terminal as a new type of input device.

In the late 1960s, GE and Bell Labs left the project. GE's computer department was bought by Honeywell, which continued the project with MIT and created a commercial version that sold for 25 years.

In 1969, Bell Labs engineers (Dennis Ritchie and Ken Thompson) developed a new OS based on Multics. In 1970, they introduced Unics (later called Unix, the name was a sarcastic play on "Multics," implying it was simpler).

The first two versions of Unix were written in assembly language, which was then translated by an assembler and linker into machine code. The big problem with assembly was that it was tightly coupled to specific processors, meaning you'd need to rewrite Unix for each processor architecture. So Dennis Ritchie decided to create a new programming language: C.

They rebuilt Unix using C. At this time, AT&T owned Bell Labs (now it's Nokia). AT&T declared that Unix was theirs and no one else could touch it, classic monopolization.

AT&T did make one merciful agreement: universities could use Unix for educational purposes. But after AT&T was broken up into smaller companies in 1984, even this stopped. Things got worse.

One person was watching all this and decided to take action: Andrew S. Tanenbaum. In 1987, he created a new Unix-inspired OS called MINIX. It was free for universities and designed to work on Intel chips. It had some issues, occasional crashes and overheating, but this was just the beginning. This was the first time someone made a Unix-like OS outside of AT&T.

The main difference between Unix and MINIX was that MINIX was built on a microkernel architecture. Unix had a larger monolithic kernel, but MINIX separated some modules, for example, device drivers were moved from kernel space to user space.

It's unclear if MINIX was truly open source, but people outside universities wanted access and wanted to contribute and modify it.

Around the same time MINIX was being developed, another person named Richard Stallman started the free software movement based on four freedoms: Freedom to run, Freedom to study, Freedom to modify, and Freedom to share. This led to the GPL license (GNU General Public License), which ensured that if you used something free, your product must also be free. They created the GNU Project, which produced many important tools like the GCC compiler, Bash shell, and more.

But there was one problem: the kernel, the beating heart of the operating system that talks to the hardware, was missing.

Let's leave the USA and cross the Atlantic Ocean. In Finland, a student named Linus Torvalds was stuck at home while his classmates vacationed in Baltim Egypt (kidding). He was frustrated with MINIX, had heard about GPL and GNU, and decided to make something new. "I know what I should do with my life," he thought. As a side hobby project in 1991, he started working on a new kernel (not based on MINIX) and sent an email to his classmates discussing it.

Linus announced Freax (maybe meant "free Unix") with a GPL license. After six months, he released another version and called it Linux. He improved the kernel and integrated many GNU Project tools. He uploaded the source code to the internet (though Git came much later, he initially used FTP). This mini-project became the most widely used OS on Earth.

The penguin mascot (Tux) came from multiple stories: Linus was supposedly bitten by a penguin at a zoo, and he also watched March of the Penguins and was inspired by how they cooperate and share to protect their eggs and each other. Cute and fitting.

...And that's the history intro.

Linux Distributions

Okay... let's install Linux. Which Linux? Wait, really? There are multiple Linuxes?

Here's the deal: the open-source part is the kernel, but different developers take it and add their own packages, libraries, and maybe create a GUI. Others add their own tweaks and features. This leads to many different versions, which we call distributions (or distros for short).

Some examples: Red Hat, Slackware, Debian.

Even distros themselves can be modified with additional features, which creates a version of a version. For example, Debian led to Ubuntu, these are called derivatives.

How many distros and derivatives exist in the world? Many. How many exactly? I said many. Anyone with a computer can create one.

So what's the main difference between these distros, so I know which one is suitable for me? The main differences fall into two categories: philosophical and technical.

One of the biggest technical differences is package management, the system that lets you install software, including the type and format of software itself.

Another difference is configuration files, their locations differ from one distro to another.

We agreed that everything is free, right? Well, you may find some paid versions like Red Hat Enterprise Linux, which charges for features like an additional layer of security, professional support, and guaranteed upgrades. Fedora is also owned by Red Hat and acts as a testing ground (a "backdoor," if you will) for new features before they hit Red Hat Enterprise.

The philosophical part is linked to the functional part. If you're using Linux for research, there are distros with specialized software for that. Maybe you're into ethical hacking, Kali Linux is for you. If you're afraid of switching from another OS, you might like Linux Mint, which even has themes that make it look like Windows.

Okay, which one should I install now? Heh... There are a ton of options and you can install any of them, but my preference is Ubuntu.

Ubuntu is the most popular for development and data engineering. But remember, in all cases, you'll be using the terminal a lot. So install Ubuntu, maybe in dual boot, and keep Windows if possible so you don't regret it later and blame me.

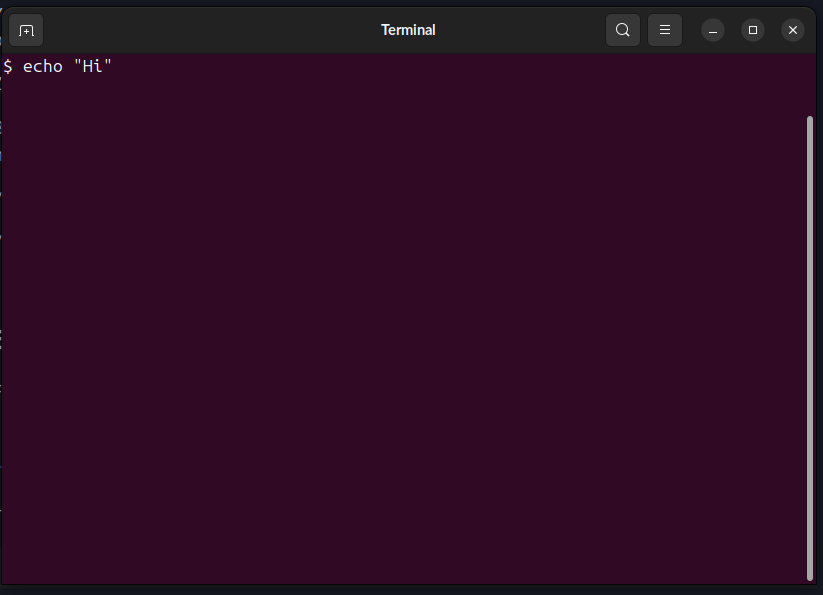

The Terminal

Yes, this is what matters for us. Every distro will come with a default terminal but you can install others if you want. Anyway, open the terminal from the apps or just click Ctrl+Alt+T.

Zoom in using Ctrl+Shift++ or out using Ctrl+-

By default first thing you will see the prompt name@host:path$ which your name @ the machine name then ~ then dollar sign colon then $. After $ you can write your command.

You can change the colors and all preferences and save each for profile.

You can even change the prompt itself as it is just a variable (more on variable later).

Basic Commands

First, everything is case sensitive, so be careful.

[1] echo

This command echoes whatever you write after it.

$ echo "Hello, terminal"

Output:

Hello, terminal

[2] pwd

This prints the current directory.

$ pwd

Output:

/home/mahmoudxyz

[3] cd

This is for changing the directory.

$ cd Desktop

The directory changed with no output, you can check this using pwd.

To go back to the main directory use:

$ cd ~

Or just:

$ cd

Note that this means we are back to /home/mahmoudxyz

To go back to the previous directory (in this case /home) even if you don't know the name, you can use:

$ cd ..

[4] ls

This command outputs the current files and directories (folders).

First let's go to desktop again:

$ cd /home/mahmoudxyz/Desktop

Yes, you can go to a specific dir if you know its path. Note that in Linux we are using / not \ like Windows.

Now let's see what files and directories are in my Desktop:

$ ls

Output:

file1 python testdir

If you notice that in my case, my terminal supports colors. The blue ones are directories and the grey (maybe black) is the file.

But you may deal with some terminal that doesn't support colors, in this case you can use:

$ ls -F

Output:

file1 python/ testdir/

What ends with / like python/ is a directory otherwise it's a file like file1.

You can see the hidden files using:

$ ls -a

Output:

. .. file1 python testdir .you-cant-see-me

We saw .you-cant-see-me, but we are not hackers that we saw something hidden, being hidden is more than organizing purpose than actually hiding something.

You can also list the files in the long format using:

$ ls -l

Output:

total 8

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 10:48 file1

drwxrwxr-x 2 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 4096 Oct 16 15:20 python

drwxrwxr-x 2 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 4096 Nov 1 21:45 testdir

Let's take the file1 and analyze the output:

| Column | Meaning |

|---|---|

-rw-rw-r-- 1 | File type + permissions (more on this later) |

1 | Number of hard links (more on this later) |

mahmoudxyz | Owner name |

mahmoudxyz | Group name |

0 | File size (bytes) |

Nov 2 10:48 | Last modification date & time |

file1 | File or directory name |

We can also combine these flags/options:

$ ls -l -a -F

Output:

total 16

drwxr-xr-x 4 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 4096 Nov 2 10:53 ./

drwxr-x--- 47 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 4096 Nov 1 21:55 ../

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 10:48 file1

drwxrwxr-x 2 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 4096 Oct 16 15:20 python/

drwxrwxr-x 2 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 4096 Nov 1 21:45 testdir/

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 10:53 .you-cant-see-me

Or shortly:

$ ls -laF

The same output. The order of options is not important so ls -lFa will work as well.

[5] clear

This cleans your terminal. You can also use shortcut Ctrl+l

[6] mkdir

This makes a new directory.

$ mkdir new-dir

Then let's see the output:

$ ls -F

Output:

file1 new-dir/ python/ testdir/

[7] rmdir

This will remove the directory.

$ rmdir new-dir

Then let's see the output:

$ ls -F

Output:

file1 python/ testdir/

[8] touch

This command is for creating a new file.

$ mkdir new-dir

$ cd new-dir

$ touch file1

$ ls -l

Output:

total 0

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:26 file1

You can also make more than one file with:

$ touch file2 file3

$ ls -l

Output:

total 0

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:26 file1

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:28 file2

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:28 file3

In fact touch was created for modifying the timestamp of the file so let's try again:

$ touch file1

$ ls -l

Output:

total 0

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:30 file1

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:28 file2

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:28 file3

What changed? The timestamp of file1. The touch is the easiest way to create a new file, it just changes the timestamp of the file and if it doesn't exist, it will create a new one.

[9] rm

This will remove the file.

$ rm file1

$ ls -l

Output:

total 0

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:28 file2

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 0 Nov 2 11:28 file3

[10] echo & cat (revisited)

Yes again, but this time, it will be used to create a new file with some text inside it.

$ echo "Hello, World" > file1

To output this file we can use:

$ cat file1

Output:

Hello, World

Notes:

- If

file1doesn't exist, it will create a new one. - If it does exist → it will be overwritten.

To append text instead of overwrite use >>:

$ echo "Hello, Mah" >> file1

To output this file we can use:

$ cat file1

Output:

Hello, World

Hello, Mah

[11] rm -r

Let's go back:

$ cd ..

And then let's try to remove the directory:

$ rmdir new-dir

Output:

rmdir: failed to remove 'new-dir': Directory not empty

In case the directory is not empty, we can use rm that we used for removing a file but this time with a flag -r which means recursively remove everything in the folder.

$ rm -r new-dir

[12] cp

This command is for copying a file.

cp source destination

(you can also rename it while copying it)

For example, let's copy the hosts file:

$ cp /etc/hosts .

The dot . means the current directory. Meaning copy this file from this source to here. You can see the content of the file using cat as before.

[13] man

man is the built-in manual for commands. It contains short descriptions for the command and its options and their functions. It is useful and can be replaced nowadays with online search or even AI.

Try:

$ man ls

And then try:

$ man cd

No manual entry for cd. I don't know why exactly, but it's probably because cd is built into the shell itself and not an external command or maybe programmer choice.

Unix Philosophy

Second System Syndrome: If a software or system succeeds, any similar system that comes after it will likely fail. This is probably a psychological phenomenon, developers constantly compare themselves to the successful system, wanting to be like it but better. The fear of not matching that success often causes failure. Maybe you can succeed if you don't compare yourself to it.

Another thing: when developers started making software for Linux, everything was chaotic and random. This led to the creation of principles to govern development, a philosophy to follow. These principles ensure that when you develop something, you follow the same Unix mentality:

- Small is Beautiful – Keep programs compact and focused; bloat is the enemy.

- Each Program Does One Thing Well – Master one task instead of being mediocre at many.

- Prototype as Soon as Possible – Build it, test it, break it, learn from it, fast iteration wins.

- Choose Portability Over Efficiency – Code that runs everywhere beats code that's blazing fast on one system.

- Store Data in Flat Text Files – Text is universal, readable, and easy to parse; proprietary formats lock you in.

- Use Software Leverage – Don't reinvent the wheel; use existing tools and combine them creatively.

- Use Shell Scripts to Increase Leverage and Portability – Automate tasks and glue programs together with simple scripts.

- Avoid Captive User Interfaces – Don't trap users in rigid menus; let them pipe, redirect, and automate.

- Make Every Program a Filter – Take input, transform it, produce output, programs should be composable building blocks.

These concepts all lead to one fundamental Unix principle: everything is a file. Devices, processes, sockets, treat them all as files for consistency and simplicity.

Not all people follow this now, but the important question is: is it important? I don't know. But still the question is: is it important for you as a data engineer or analyst who will deal with data and different distros and different computers which maybe will be remote? Yes, it is important and very important.

Text Files

It's a bit strange that we are talking about editing text files in 2025. Really, does it matter?

Yes, it matters and it's a big topic in Linux because of what we discussed in the previous section.

There are a lot of editors on Linux like vi, nano and emacs. There is a famous debate between emacs and vim.

You can find vi in almost every distro. The shortcuts for it are many and hard to memorize if you are not dealing with it much, but you can use cheatsheets.

Simply put: vi is just two things, insert mode and command mode. The default when you open a file for the first time is the command mode. To start writing something you have to enter the insert mode by pressing i.

You might wonder why vi uses keyboard letters for navigation instead of arrow keys. Simple answer: arrow keys didn't exist on keyboards when vi was created in 1976. You're the lucky generation with arrow keys, the original vi users had to make do with what they had.

nano on the other hand is more simple and easier to use and edit files with.

Use any editor, probably vi or nano and start practicing on one.

Terminal vs Shell

Terminal ≠ Shell. Let's clear this up.

The shell is the thing that actually interprets your commands. It's the engine doing the work. File manipulation, running programs, printing text. That's all the shell.

The terminal is just the program that opens a window so you can talk to the shell. It's the middleman, the GUI wrapper, the pretty face.

This distinction mattered more when terminals were physical devices, actual hardware connected to mainframes. Today, we use terminal emulators (software), so the difference is mostly semantic. For practical purposes, just know: the shell runs your commands, the terminal displays them.

Pipes, Filters and Redirection

Standard Streams

Unix processes use I/O streams to read and write data.

Input stream sources include keyboards, terminals, devices, files, output from other processes, etc.

Unix processes have three standard streams:

- STDIN (0) – Standard Input (data coming in from keyboard, file, etc.)

- STDOUT (1) – Standard Output (normal output going to terminal, file, etc.)

- STDERR (2) – Standard Error (error messages going to terminal, file, etc.)

Example: Try running cat with no arguments, it waits for input from STDIN and echoes it to STDOUT.

Ctrl+D– Stops the input stream and sends an EOF (End of File) signal to the process.Ctrl+C– Sends an INT (Interrupt) signal to the process (i.e., kills the process).

Redirection

Redirection allows you to change the defaults for stdin, stdout, or stderr, sending them to different devices or files using their file descriptors.

File Descriptors

A file descriptor is a reference (or handle) used by the kernel to access a file. Every process gets its own file descriptor table.

Redirect stdin with <

Use the < operator to redirect standard input from a file:

$ wc < textfile

Using Heredocs with <<

Accepts input until a specified delimiter word is reached:

$ cat << EOF

# Type multiple lines here

# Press Enter, then type EOF to end

EOF

Using Herestrings with <<<

Pass a string directly as input:

$ cat <<< "Hello, Linux"

Redirect stdout using > and >>

Overwrite a file with > (or explicitly with 1>):

$ who > file # Redirect stdout to file (overwrite)

$ cat file # View the file

Append to a file with >>:

$ whoami >> file # Append stdout to file

$ cat file # View the file

Redirect stderr using 2> and 2>>

Redirect error messages to a file:

$ ls /xyz 2> err # /xyz doesn't exist, error goes to err file

$ cat err # View the error

Combining stdout and stderr

Redirect both stdout and stderr to the same file:

# Method 1: Redirect stderr to err, then stdout to the same place

$ ls /etc /xyz 2> err 1>&2

# Method 2: Redirect stdout to err, then stderr to the same place

$ ls /etc /xyz 1> err 2>&1

# Method 3: Shorthand for redirecting both

$ ls /etc /xyz &> err

$ cat err # View both output and errors

Ignoring Error Messages with /dev/null

The black hole of Unix, anything sent here disappears:

$ ls /xyz 2> /dev/null # Suppress error messages

User and Group Management

It is not complicated. The user here is like any other OS. An account with some permission and can do some operations.

There are three types of users in Linux:

Super user

The administrator that can do anything in the world. It is called root.

- ID from 0 to 999

System user

This represents software and not a real person. Some software may need some access and permissions to do some tasks and operations or maybe install something.

- ID from 0 to 999

Normal user

This is us.

- ID >= 1000

Each user has its ID, shell, environmental vars and home dir.

File Ownership and Permissions

(Content to be added)

More on Navigating the Filesystem

Absolute vs Relative Paths

The root directory (/) is like "C:" in Windows, the top of the filesystem hierarchy.

Absolute path: Starts from root, always begins with /

/home/mahmoudxyz/Documents/notes.txt

/etc/passwd

/usr/bin/python3

Relative path: Starts from your current location

Documents/notes.txt # Relative to current directory

../Desktop/file.txt # Go up one level, then into Desktop

../../etc/hosts # Go up two levels, then into etc

Special directory references:

.= current directory..= parent directory~= your home directory-= previous directory (used withcd -)

Useful Navigation Commands

ls -lh - List in long format with human-readable sizes

$ ls -lh

-rw-r--r-- 1 mahmoud mahmoud 1.5M Nov 10 14:23 data.csv

-rw-r--r-- 1 mahmoud mahmoud 12K Nov 10 14:25 notes.txt

ls -lhd - Show directory itself, not contents

$ ls -lhd /home/mahmoud

drwxr-xr-x 47 mahmoud mahmoud 4.0K Nov 10 12:00 /home/mahmoud

ls -lR - Recursive listing (all subdirectories)

$ ls -lR

./Documents:

-rw-r--r-- 1 mahmoud mahmoud 1234 Nov 10 14:23 file1.txt

./Documents/Projects:

-rw-r--r-- 1 mahmoud mahmoud 5678 Nov 10 14:25 file2.txt

tree - Visual directory tree (may need to install)

$ tree

.

├── Documents

│ ├── file1.txt

│ └── Projects

│ └── file2.txt

├── Downloads

└── Desktop

stat - Detailed file information

$ stat notes.txt

File: notes.txt

Size: 1234 Blocks: 8 IO Block: 4096 regular file

Device: 803h/2051d Inode: 12345678 Links: 1

Access: 2024-11-10 14:23:45.123456789 +0100

Modify: 2024-11-10 14:23:45.123456789 +0100

Change: 2024-11-10 14:23:45.123456789 +0100

Shows: size, inode number, links, permissions, timestamps

Shell Globbing (Wildcards)

Wildcards let you match multiple files with patterns.

* - Matches any number of any characters (including none)

$ echo * # All files in current directory

$ echo *.txt # All files ending with .txt

$ echo file* # All files starting with "file"

$ echo *data* # All files containing "data"

? - Matches exactly one character

$ echo b?at # Matches: boat, beat, b1at, b@at

$ echo file?.txt # Matches: file1.txt, fileA.txt

$ echo ??? # Matches any 3-character filename

[...] - Matches any character inside brackets

$ echo file[123].txt # Matches: file1.txt, file2.txt, file3.txt

$ echo [a-z]* # Files starting with lowercase letter

$ echo [A-Z]* # Files starting with uppercase letter

$ echo *[0-9] # Files ending with a digit

[!...] - Matches any character NOT in brackets

$ echo [!a-z]* # Files NOT starting with lowercase letter

$ echo *[!0-9].txt # .txt files NOT ending with a digit before extension

Practical examples:

$ ls *.jpg *.png # All image files (jpg or png)

$ rm temp* # Delete all files starting with "temp"

$ cp *.txt backup/ # Copy all text files to backup folder

$ mv file[1-5].txt archive/ # Move file1.txt through file5.txt

File Structure: The Three Components

Every file in Linux consists of three parts:

1. Filename

The human-readable name you see and use.

2. Data Block

The actual content stored on disk, the file's data.

3. Inode (Index Node)

Metadata about the file stored in a data structure. Contains:

- File size

- Owner (UID) and group (GID)

- Permissions

- Timestamps (access, modify, change)

- Number of hard links

- Pointers to data blocks on disk

- NOT the filename (filenames are stored in directory entries)

View inode number:

$ ls -i

12345678 file1.txt

12345679 file2.txt

View detailed inode information:

$ stat file1.txt

Links: Hard Links vs Soft Links

What is a Link?

A link is a way to reference the same file from multiple locations. Think of it like shortcuts in Windows, but with two different types.

Hard Links

Concept: Another filename pointing to the same inode and data.

It's like having two labels on the same box. Both names are equally valid, neither is "original" or "copy."

Create a hard link:

$ ln original.txt hardlink.txt

What happens:

- Both filenames point to the same inode

- Both have equal status (no "original")

- Changing content via either name affects both (same data)

- File size, permissions, content are identical (because they ARE the same file)

Check with ls -i:

$ ls -i

12345678 original.txt

12345678 hardlink.txt # Same inode number!

What if you delete the original?

$ rm original.txt

$ cat hardlink.txt # Still works! Data is intact

Why? The data isn't deleted until all hard links are removed. The inode keeps a link count, only when it reaches 0 does the system delete the data.

Limitations of hard links:

- Cannot cross filesystems (different partitions/drives)

- Cannot link to directories (to prevent circular references)

- Both files must be on the same partition

Soft Links (Symbolic Links)

Concept: A special file that points to another filename, like a shortcut in Windows.

The soft link has its own inode, separate from the target file.

Create a soft link:

$ ln -s original.txt softlink.txt

What happens:

softlink.txthas a different inode- It contains the path to

original.txt - Reading

softlink.txtautomatically redirects tooriginal.txt

Check with ls -li:

$ ls -li

12345678 -rw-r--r-- 1 mahmoud mahmoud 100 Nov 10 14:00 original.txt

12345680 lrwxrwxrwx 1 mahmoud mahmoud 12 Nov 10 14:01 softlink.txt -> original.txt

Notice:

- Different inode numbers

lat the start (link file type)->shows what it points to

What if you delete the original?

$ rm original.txt

$ cat softlink.txt # Error: No such file or directory

The softlink still exists, but it's now a broken link (points to nothing).

Advantages of soft links:

- Can cross filesystems (different partitions/drives)

- Can link to directories

- Can link to files that don't exist yet (forward reference)

Hard Link vs Soft Link: Summary

| Feature | Hard Link | Soft Link |

|---|---|---|

| Inode | Same as original | Different (own inode) |

| Content | Points to data | Points to filename |

| Delete original | Link still works | Link breaks |

| Cross filesystems | No | Yes |

| Link to directories | No | Yes |

| Shows target | No (looks like normal file) | Yes (-> in ls -l) |

| Link count | Increases | Doesn't affect original |

When to use each:

Hard links:

- Backup/versioning within same filesystem

- Ensure file persists even if "original" name is deleted

- Save space (no duplicate data)

Soft links:

- Link across different partitions

- Link to directories

- Create shortcuts for convenience

- When you want the link to break if target is moved/deleted (intentional dependency)

Practical Examples

Hard link example:

$ echo "Important data" > data.txt

$ ln data.txt backup.txt # Create hard link

$ rm data.txt # "Original" deleted

$ cat backup.txt # Still accessible!

Important data

Soft link example:

$ ln -s /usr/bin/python3 ~/python # Shortcut to Python

$ ~/python --version # Works!

Python 3.10.0

$ rm /usr/bin/python3 # If Python is removed

$ ~/python --version # Link breaks

bash: ~/python: No such file or directory

Link to directory (only soft link):

$ ln -s /var/log/nginx ~/nginx-logs # Easy access to logs

$ cd ~/nginx-logs # Navigate via link

$ pwd # Shows real path

/var/log/nginx

Understanding the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard

Mounting

There's no link between the hierarchy of directories and their location on the disk.

For more details, see: Linux Foundation FHS 3.0

File Management

[1] grep

This command to print lines matching pattern

Let's create a file to try examples on it:

echo -e "root\nhello\nroot\nRoot" >> file

Now let's use grep to search for the word root in this file:

$ grep root file

output:

root

root

You can search for anything excluding the root word:

$ grep -v root file

output:

hello

Root

You can search ingoring the case:

$ grep -i root file

result:

root

root

Root

You can also use REGEX:

$ grep -i r. file

result:

root

root

Root

[2] less

to page through a file (an alternative to more)

-- use with /word to search for a word in the file -- use with ?word to search backwards for a word in the file -- use with n to go to the next occurrence of the word -- use with N to go to the previous occurrence of the word -- use with q to quit the file

[3] diff

compare files line by line

[4] file

determine file type

$ file file

file: ASCII text

[5] find and locate

search for files in a directory hierarchy

[6] head and tail

head - output the first part of files head /usr/share/dict/words - display the first 10 lines of the file /usr/share/dict/words head -n 20 /usr/share/dict/words - display the first 20 lines of the file /usr/share/dict/words

tail - output the last part of files tail /usr/share/dict/words - display the last 10 lines of the file /usr/share/dict/words tail -n 20 /usr/share/dict/words - display the last 20 lines of the file /usr/share/dict/words

[7] mv

mv - move (rename) files mv file1 file2 - rename file1 to file2

mv - move (rename) files mv file1 file2 - rename file1 to file2

[8] cp

cp - copy files and directories cp file1 file2 - copy file1 to file2

[9] tar

archive utility

[10] gzip

[11] mount and unmount

what is the meaning of mounitng

Managing Linux Processes

What is a Process?

When Linux executes a program, it:

- Reads the file from disk

- Loads it into memory

- Reads the instructions inside it

- Executes them one by one

A process is the running instance of that program. It might be visible in your GUI or running invisibly in the background.

Types of Processes

Processes can be executed from different sources:

By origin:

- Compiled programs (C, C++, Rust, etc.)

- Shell scripts containing commands

- Interpreted languages (Python, Perl, etc.)

By trigger:

- Manually executed by a user

- Scheduled (via cron or systemd timers)

- Triggered by events or other processes

By category:

- System processes - Managed by the kernel

- User processes - Started by users (manually, scheduled, or remotely)

The Process Hierarchy

Every Linux system starts with a parent process that spawns all other processes. This is either:

initorsysvinit(older systems)systemd(modern systems)

The first process gets PID 1 (Process ID 1), even though it's technically branched from the kernel itself (PID 0, which you never see directly).

From PID 1, all other processes branch out in a tree structure. Every process has:

- PID (Process ID) - Its own unique identifier

- PPID (Parent Process ID) - The ID of the process that started it

Viewing Processes

[1] ps - Process Snapshot

Basic usage - current terminal only:

$ ps

Output:

PID TTY TIME CMD

14829 pts/1 00:00:00 bash

14838 pts/1 00:00:00 ps

This shows only processes running in your current terminal session for your user.

All users' processes:

$ ps -a

Output:

PID TTY TIME CMD

2955 tty2 00:00:00 gnome-session-b

14971 pts/1 00:00:00 ps

All processes in the system:

$ ps -e

Output:

PID TTY TIME CMD

1 ? 00:00:00 systemd

2 ? 00:00:00 kthreadd

3 ? 00:00:00 rcu_gp

... (hundreds more)

Note: The ? in the TTY column means the process was started by the kernel and has no controlling terminal.

Detailed process information:

$ ps -l

Output:

F S UID PID PPID C PRI NI ADDR SZ WCHAN TTY TIME CMD

0 S 1000 14829 14821 0 80 0 - 2865 do_wai pts/1 00:00:00 bash

4 R 1000 15702 14829 0 80 0 - 3445 - pts/1 00:00:00 ps

Here you can see the PPID (parent process ID). Notice that ps has bash as its parent (the PPID of ps matches the PID of bash).

Most commonly used:

$ ps -efl

This shows all processes with full details - PID, PPID, user, CPU time, memory, and command.

Understanding Daemons

Any system process running in the background typically ends with d (named after "daemon"). Examples:

systemd- System and service managersshd- SSH serverhttpdornginx- Web serverscrond- Job scheduler

Daemons are like Windows services - processes that run in the background, whether they're system or user processes.

[2] pstree - Process Tree Visualization

See the hierarchy of all running processes:

$ pstree

Output:

systemd─┬─ModemManager───3*[{ModemManager}]

├─NetworkManager───3*[{NetworkManager}]

├─accounts-daemon───3*[{accounts-daemon}]

├─avahi-daemon───avahi-daemon

├─bluetoothd

├─colord───3*[{colord}]

├─containerd───15*[{containerd}]

├─cron

├─cups-browsed───3*[{cups-browsed}]

├─cupsd───5*[dbus]

├─dbus-daemon

├─dockerd───19*[{dockerd}]

├─fwupd───5*[{fwupd}]

... (continues)

What you're seeing:

systemdis the parent process (PID 1)- Everything else branches from it

- Multiple processes run in parallel

- Some processes spawn their own children (like

dockerdwith 19 threads)

This visualization makes it easy to understand process relationships.

[3] top - Live Process Monitor

Unlike ps (which shows a snapshot), top shows real-time process information:

$ top

You'll see:

- Processes sorted by CPU usage (by default)

- Live updates of CPU and memory consumption

- System load averages

- Running vs sleeping processes

Press q to quit.

Useful top commands while running:

k- Kill a process (prompts for PID)M- Sort by memory usageP- Sort by CPU usage1- Show individual CPU coresh- Help

[4] htop - Better Process Monitor

htop is like top but modern, colorful, and more interactive.

Installation (if not already installed):

$ which htop # Check if installed

$ sudo apt install htop # Install if needed

Run it:

$ htop

Features:

- Color-coded display

- Mouse support (click to select processes)

- Easy process filtering and searching

- Visual CPU and memory bars

- Tree view of process hierarchy

- Built-in kill/nice/priority management

Navigation:

- Arrow keys to move

F3- Search for a processF4- Filter by nameF5- Tree viewF9- Kill a processF10orq- Quit

Foreground vs Background Processes

Sometimes you only have one terminal and want to run multiple long-running tasks. Background processes let you do this.

Foreground Processes (Default)

When you run a command normally, it runs in the foreground and blocks your terminal:

$ sleep 10

Your terminal is blocked for 10 seconds. You can't type anything until it finishes.

Background Processes

Add & at the end to run in the background:

$ sleep 10 &

Output:

[1] 12345

The terminal is immediately available. The numbers show [job_number] PID.

Managing Jobs

View running jobs:

$ jobs

Output:

[1]+ Running sleep 10 &

Bring a background job to foreground:

$ fg

If you have multiple jobs:

$ fg %1 # Bring job 1 to foreground

$ fg %2 # Bring job 2 to foreground

Send current foreground process to background:

- Press

Ctrl+Z(suspends the process) - Type

bg(resumes it in background)

Example:

$ sleep 25

^Z

[1]+ Stopped sleep 25

$ bg

[1]+ sleep 25 &

$ jobs

[1]+ Running sleep 25 &

Stopping Processes

Process Signals

The kill command doesn't just "kill" - it sends signals to processes. The process decides how to respond.

Common signals:

| Signal | Number | Meaning | Process Can Ignore? |

|---|---|---|---|

SIGHUP | 1 | Hang up (terminal closed) | Yes |

SIGINT | 2 | Interrupt (Ctrl+C) | Yes |

SIGTERM | 15 | Terminate gracefully (default) | Yes |

SIGKILL | 9 | Kill immediately | NO |

SIGSTOP | 19 | Stop/pause process | NO |

SIGCONT | 18 | Continue stopped process | NO |

Using kill

Syntax:

$ kill -SIGNAL PID

Example - find a process:

$ ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

14829 pts/1 00:00:00 bash

17584 pts/1 00:00:00 sleep

18865 pts/1 00:00:00 ps

Try graceful termination first (SIGTERM):

$ kill -SIGTERM 17584

Or use the number:

$ kill -15 17584

Or just use default (SIGTERM is default):

$ kill 17584

If the process ignores SIGTERM, force kill (SIGKILL):

$ kill -SIGKILL 17584

Or:

$ kill -9 17584

Verify it's gone:

$ ps

PID TTY TIME CMD

14829 pts/1 00:00:00 bash

19085 pts/1 00:00:00 ps

[2]+ Killed sleep 10

Why SIGTERM vs SIGKILL?

SIGTERM (15) - Graceful shutdown:

- Process can clean up (save files, close connections)

- Child processes are also terminated properly

- Always try this first

SIGKILL (9) - Immediate death:

- Process cannot ignore or handle this signal

- No cleanup happens

- Can create zombie processes if parent doesn't reap children

- Can cause memory leaks or corrupted files

- Use only as last resort

Zombie Processes

A zombie is a dead process that hasn't been cleaned up by its parent.

What happens:

- Process finishes execution

- Kernel marks it as terminated

- Parent should read the exit status (called "reaping")

- If parent doesn't reap it, it becomes a zombie

Identifying zombies:

$ ps aux | grep Z

Look for processes with state Z (zombie).

Fixing zombies:

- Kill the parent process (zombies are already dead)

- The parent's death forces the kernel to reclassify zombies under

init/systemd, which cleans them up - Or wait - some zombies disappear when the parent finally checks on them

killall - Kill by Name

Instead of finding PIDs, kill all processes with a specific name:

$ killall sleep

This kills ALL processes named sleep, regardless of their PID.

With signals:

$ killall -SIGTERM firefox

$ killall -9 chrome # Force kill all Chrome processes

Warning: Be careful with killall - it affects all matching processes, even ones you might not want to kill.

Managing Services with systemctl

Modern Linux systems use systemd to manage services (daemons). The systemctl command controls them.

Service Status

Check if a service is running:

$ systemctl status ssh

Output shows:

- Active/inactive status

- PID of the main process

- Recent log entries

- Memory and CPU usage

Starting and Stopping Services

Start a service:

$ sudo systemctl start nginx

Stop a service:

$ sudo systemctl stop nginx

Restart a service (stop then start):

$ sudo systemctl restart nginx

Reload configuration without restarting:

$ sudo systemctl reload nginx

Enable/Disable Services at Boot

Enable a service to start automatically at boot:

$ sudo systemctl enable ssh

Disable a service from starting at boot:

$ sudo systemctl disable ssh

Enable AND start immediately:

$ sudo systemctl enable --now nginx

Listing Services

List all running services:

$ systemctl list-units --type=service --state=running

List all services (running or not):

$ systemctl list-units --type=service --all

List enabled services:

$ systemctl list-unit-files --type=service --state=enabled

Viewing Logs

See logs for a specific service:

$ journalctl -u nginx

Follow logs in real-time:

$ journalctl -u nginx -f

See only recent logs:

$ journalctl -u nginx --since "10 minutes ago"

Practical Examples

Example 1: Finding and Killing a Hung Process

# Find the process

$ ps aux | grep firefox

# Kill it gracefully

$ kill 12345

# Wait a few seconds, check if still there

$ ps aux | grep firefox

# Force kill if necessary

$ kill -9 12345

Example 2: Running a Long Script in Background

# Start a long-running analysis

$ python analyze_genome.py &

# Check it's running

$ jobs

# Do other work...

# Bring it back to see output

$ fg

Example 3: Checking System Load

# See what's consuming resources

$ htop

# Or check load average

$ uptime

# Or see top CPU processes

$ ps aux --sort=-%cpu | head

Example 4: Restarting a Web Server

# Check status

$ systemctl status nginx

# Restart it

$ sudo systemctl restart nginx

# Check logs if something went wrong

$ journalctl -u nginx -n 50

Summary: Process Management Commands

| Command | Purpose |

|---|---|

ps | Snapshot of processes |

ps -efl | All processes with details |

pstree | Process hierarchy tree |

top | Real-time process monitor |

htop | Better real-time monitor |

jobs | List background jobs |

fg | Bring job to foreground |

bg | Continue job in background |

command & | Run command in background |

Ctrl+Z | Suspend current process |

kill PID | Send SIGTERM to process |

kill -9 PID | Force kill process |

killall name | Kill all processes by name |

systemctl status | Check service status |

systemctl start | Start a service |

systemctl stop | Stop a service |

systemctl restart | Restart a service |

systemctl enable | Enable at boot |

Shell Scripts (Bash Scripting)

A shell script is simply a collection of commands written in a text file. That's it. Nothing magical.

The original name was "shell script," but when GNU created bash (Bourne Again SHell), the term "bash script" became common.

Why Shell Scripts Matter

1. Automation

If you're typing the same commands repeatedly, write them once in a script.

2. Portability

Scripts work across different Linux machines and distributions (mostly).

3. Scheduling

Combine scripts with cron jobs to run tasks automatically.

4. DRY Principle

Don't Repeat Yourself - write once, run many times.

Important: Nothing new here. Everything you've already learned about Linux commands applies. Shell scripts just let you organize and automate them.

Creating Your First Script

Create a file called first-script.sh:

$ nano first-script.sh

Write some commands:

echo "Hello, World"

Note: The .sh extension doesn't technically matter in Linux (unlike Windows), but it's convention. Use it so humans know it's a shell script.

Making Scripts Executable

Check the current permissions:

$ ls -l first-script.sh

Output:

-rw-rw-r-- 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 21 Nov 6 07:21 first-script.sh

Notice: No x (execute) permission. The file isn't executable yet.

Adding Execute Permission

$ chmod +x first-script.sh

Permission options:

u+x- Execute for user (owner) onlyg+x- Execute for group onlyo+x- Execute for others onlya+xor just+x- Execute for all (user, group, others)

Check permissions again:

$ ls -l first-script.sh

Output:

-rwxrwxr-x 1 mahmoudxyz mahmoudxyz 21 Nov 6 07:21 first-script.sh

Now we have x for user, group, and others.

Running Shell Scripts

There are two main ways to execute a script:

Method 1: Specify the Shell

$ sh first-script.sh

Or:

$ bash first-script.sh

This explicitly tells which shell to use.

Method 2: Direct Execution

$ ./first-script.sh

Why the ./ ?

Let's try without it:

$ first-script.sh

You'll get an error:

first-script.sh: command not found

Why? When you type a command without a path, the shell searches through directories listed in $PATH looking for that command. Your current directory (.) is usually NOT in $PATH for security reasons.

The ./ explicitly says: "Run the script in the current directory (.), don't search $PATH."

Adding Current Directory to PATH (NOT RECOMMENDED)

You could do this:

$ PATH=.:$PATH

Now first-script.sh would work without ./, but DON'T DO THIS. It's a security risk - you might accidentally execute malicious scripts in your current directory.

Best practices:

- Use

./script.shfor local scripts - Put system-wide scripts in

/usr/local/bin(which IS in $PATH)

The Shebang Line

Problem: How does the system know which interpreter to use for your script? Bash? Zsh? Python?

Solution: The shebang (#!) on the first line.

Basic Shebang

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello, World"

What this means:

"Execute this script using /bin/bash"

When you run ./first-script.sh, the system:

- Reads the first line

- Sees

#!/bin/bash - Runs

/bin/bash first-script.sh

Shebang with Other Languages

You can use shebang for any interpreted language:

#!/usr/bin/python3

print("Hello, World")

Now this file runs as a Python script!

The Portable Shebang

Problem: What if bash isn't at /bin/bash? What if python3 is at /usr/local/bin/python3 instead of /usr/bin/python3?

Solution: Use env to find the interpreter:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

echo "Hello, World"

Or for Python:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

print("Hello, World")

How it works:

env searches through $PATH to find the command. The shebang becomes: "Please find (env) where bash is located and execute this script with it."

Why env is better:

- More portable across systems

- Finds interpreters wherever they're installed

envitself is almost always at/usr/bin/env

Basic Shell Syntax

Command Separators

Semicolon (;) - Run commands sequentially:

$ echo "Hello" ; ls

This runs echo, then runs ls (regardless of whether echo succeeded).

AND (&&) - Run second command only if first succeeds:

$ echo "Hello" && ls

If echo succeeds (exit code 0), then run ls. If it fails, stop.

OR (||) - Run second command only if first fails:

$ false || ls

If false fails (exit code non-zero), then run ls. If it succeeds, stop.

Practical example:

$ cd /some/directory && echo "Changed directory successfully"

Only prints the message if cd succeeded.

$ cd /some/directory || echo "Failed to change directory"

Only prints the message if cd failed.

Variables

Variables store data that you can use throughout your script.

Declaring Variables

#!/bin/bash

# Integer variable

declare -i sum=16

# String variable

declare name="Mahmoud"

# Constant (read-only)

declare -r PI=3.14

# Array

declare -a names=()

names[0]="Alice"

names[1]="Bob"

names[2]="Charlie"

Key points:

declare -i= integer typedeclare -r= read-only (constant)declare -a= array- You can also just use

sum=16withoutdeclare(it works, but less explicit)

Using Variables

Access variables with $:

echo $sum # Prints: 16

echo $name # Prints: Mahmoud

echo $PI # Prints: 3.14

For arrays and complex expressions, use ${}:

echo ${names[0]} # Prints: Alice

echo ${names[1]} # Prints: Bob

echo ${names[2]} # Prints: Charlie

Why ${} matters:

echo "$nameTest" # Looks for variable called "nameTest" (doesn't exist)

echo "${name}Test" # Prints: MahmoudTest (correct!)

Important Script Options

set -e

What it does: Exit script immediately if any command fails (non-zero exit code).

Why it matters: Prevents cascading errors. If step 1 fails, don't continue to step 2.

Example without set -e:

cd /nonexistent/directory

rm -rf * # DANGER! This still runs even though cd failed

Example with set -e:

set -e

cd /nonexistent/directory # Script stops here if this fails

rm -rf * # Never executes

Exit Codes

Every command returns an exit code:

0= Success- Non-zero = Failure (different numbers mean different errors)

Check the last command's exit code:

$ true

$ echo $? # Prints: 0

$ false

$ echo $? # Prints: 1

In scripts, explicitly exit with a code:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Script completed successfully"

exit 0 # Return 0 (success) to the calling process

Arithmetic Operations

There are multiple ways to do math in bash. Pick one and stick with it for consistency.

Method 1: $(( )) (Recommended)

#!/bin/bash

num=4

echo $((num * 5)) # Prints: 20

echo $((num + 10)) # Prints: 14

echo $((num ** 2)) # Prints: 16 (exponentiation)

Operators:

+addition-subtraction*multiplication/integer division%modulo (remainder)**exponentiation

Pros: Built into bash, fast, clean syntax

Cons: Integer-only (no decimals)

Method 2: expr

#!/bin/bash

num=4

expr $num + 6 # Prints: 10

expr $num \* 5 # Prints: 20 (note the backslash before *)

Pros: Traditional, works in older shells

Cons: Awkward syntax, needs escaping for *

Method 3: bc (For Floating Point)

#!/bin/bash

echo "4.5 + 2.3" | bc # Prints: 6.8

echo "10 / 3" | bc -l # Prints: 3.33333... (-l for decimals)

echo "scale=2; 10/3" | bc # Prints: 3.33 (2 decimal places)

Pros: Supports floating-point arithmetic

Cons: External program (slower), more complex

My recommendation: Use $(( )) for most cases. Use bc when you need decimals.

Logical Operations and Conditionals

Exit Code Testing

#!/bin/bash

true ; echo $? # Prints: 0

false ; echo $? # Prints: 1

Logical Operators

true && echo "True" # Prints: True (because true succeeds)

false || echo "False" # Prints: False (because false fails)

Comparison Operators

There are TWO syntaxes for comparisons in bash. Stick to one.

Option 1: [[ ]] with Comparison Operators (Modern, Recommended)

For integers:

[[ 1 -le 2 ]] # Less than or equal

[[ 3 -ge 2 ]] # Greater than or equal

[[ 5 -lt 10 ]] # Less than

[[ 8 -gt 4 ]] # Greater than

[[ 5 -eq 5 ]] # Equal

[[ 5 -ne 3 ]] # Not equal

For strings and mixed:

[[ 3 == 3 ]] # Equal

[[ 3 != 4 ]] # Not equal

[[ 5 > 3 ]] # Greater than (lexicographic for strings)

[[ 2 < 9 ]] # Less than (lexicographic for strings)

Testing the result:

[[ 3 == 3 ]] ; echo $? # Prints: 0 (true)

[[ 3 != 3 ]] ; echo $? # Prints: 1 (false)

[[ 5 > 3 ]] ; echo $? # Prints: 0 (true)

Option 2: test Command (Traditional)

test 1 -le 5 ; echo $? # Prints: 0 (true)

test 10 -lt 5 ; echo $? # Prints: 1 (false)

test is equivalent to [ ] (note: single brackets):

[ 1 -le 5 ] ; echo $? # Same as test

My recommendation: Use [[ ]] (double brackets). It's more powerful and less error-prone than [ ] or test.

File Test Operators

Check file properties:

test -f /etc/hosts ; echo $? # Does file exist? (0 = yes)

test -d /home ; echo $? # Is it a directory? (0 = yes)

test -r /etc/shadow ; echo $? # Do I have read permission? (1 = no)

test -w /tmp ; echo $? # Do I have write permission? (0 = yes)

test -x /usr/bin/ls ; echo $? # Is it executable? (0 = yes)

Common file tests:

-ffile exists and is a regular file-ddirectory exists-eexists (any type)-rreadable-wwritable-xexecutable-sfile exists and is not empty

Using [[ ]] syntax:

[[ -f /etc/hosts ]] && echo "File exists"

[[ -r /etc/shadow ]] || echo "Cannot read this file"

Positional Parameters (Command-Line Arguments)

When you run a script with arguments, bash provides special variables to access them.

Special Variables

#!/bin/bash

# $0 - Name of the script itself

# $# - Number of command-line arguments

# $* - All arguments as a single string

# $@ - All arguments as separate strings (array-like)

# $1 - First argument

# $2 - Second argument

# $3 - Third argument

# ... and so on

Example Script

#!/bin/bash

echo "Script name: $0"

echo "Total number of arguments: $#"

echo "All arguments: $*"

echo "First argument: $1"

echo "Second argument: $2"

Running it:

$ ./script.sh hello world 123

Output:

Script name: ./script.sh

Total number of arguments: 3

All arguments: hello world 123

First argument: hello

Second argument: world

$* vs $@

$* - Treats all arguments as a single string:

for arg in "$*"; do

echo $arg

done

# Output: hello world 123 (all as one)

$@ - Treats arguments as separate items:

for arg in "$@"; do

echo $arg

done

# Output:

# hello

# world

# 123

Recommendation: Use "$@" when looping through arguments.

Functions

Functions let you organize code into reusable blocks.

Basic Function

#!/bin/bash

Hello() {

echo "Hello Functions!"

}

Hello # Call the function

Alternative syntax:

function Hello() {

echo "Hello Functions!"

}

Both work the same. Pick one style and be consistent.

Functions with Return Values

#!/bin/bash

function Hello() {

echo "Hello Functions!"

return 0 # Success

}

function GetTimestamp() {

echo "The time now is $(date +%m/%d/%y' '%R)"

return 0

}

Hello

echo "Exit code: $?" # Prints: 0

GetTimestamp

Important: return only returns exit codes (0-255), NOT values like other languages.

To return a value, use echo:

function Add() {

local result=$(($1 + $2))

echo $result # "Return" the value via stdout

}

sum=$(Add 5 3) # Capture the output

echo "Sum: $sum" # Prints: Sum: 8

Function Arguments

Functions can take arguments like scripts:

#!/bin/bash

Greet() {

echo "Hello, $1!" # $1 is first argument to function

}

Greet "Mahmoud" # Prints: Hello, Mahmoud!

Greet "World" # Prints: Hello, World!

Reading User Input

Basic read Command

#!/bin/bash

echo "What is your name?"

read name

echo "Hello, $name!"

How it works:

- Script displays prompt

- Waits for user to type and press Enter

- Stores input in variable

name

read with Inline Prompt

#!/bin/bash

read -p "What is your name? " name

echo "Hello, $name!"

-p flag: Display prompt on same line as input

Reading Multiple Variables

#!/bin/bash

read -p "Enter your first and last name: " first last

echo "Hello, $first $last!"

Input: Mahmoud Xyz

Output: Hello, Mahmoud Xyz!

Reading Passwords (Securely)

#!/bin/bash

read -sp "Enter your password: " password

echo "" # New line after hidden input

echo "Password received (length: ${#password})"

-s flag: Silent mode - doesn't display what user types

-p flag: Inline prompt

Security note: This hides the password from screen, but it's still in memory as plain text. For real password handling, use dedicated tools.

Reading from Files

#!/bin/bash

while read line; do

echo "Line: $line"

done < /etc/passwd

Reads /etc/passwd line by line.

Best Practices

- Always use shebang:

#!/usr/bin/env bash - Use

set -e: Stop on errors - Use

set -u: Stop on undefined variables - Use

set -o pipefail: Catch errors in pipes - Quote variables: Use

"$var"not$var(prevents word splitting) - Check return codes: Test if commands succeeded

- Add comments: Explain non-obvious logic

- Use functions: Break complex scripts into smaller pieces

- Test thoroughly: Run scripts in safe environment first

The Holy Trinity of Safety

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -euo pipefail

-eexit on error-uexit on undefined variable-o pipefailexit on pipe failures

About Course Materials

These notes contain NO copied course materials. Everything here is my personal understanding and recitation of concepts, synthesized from publicly available resources (bash documentation, shell scripting tutorials, Linux guides).

This is my academic work, how I've processed and reorganized information from legitimate sources. I take full responsibility for any errors in my understanding.

If you believe any content violates copyright, contact me at mahmoudahmedxyz@gmail.com and I'll remove it immediately.

References

[1] Ahmed Sami (Architect @ Microsoft).

Linux for Data Engineers (Arabic – Egyptian Dialect), 11h 30m.

YouTube

Python

I don't like cheat sheets. What we really need is daily problem-solving. Read other people's code, understand how they think - this is the only real way to improve.

This is a quick overview combined with practice problems. Things might appear in a reversed order sometimes - we'll introduce concepts by solving problems and covering tools as needed.

If you need help setting up something, write me.

Resources

Free Books:

If you want to buy:

Your First Program

print("Hello, World!")

print() works. Print() does not!

The print() Function

Optional arguments: sep and end

sep (separator) - what goes between values:

print("A", "B", "C") # A B C (default: space)

print("A", "B", "C", sep="-") # A-B-C

print(1, 2, 3, sep=" | ") # 1 | 2 | 3

end - what prints after the line:

print("Hello")

print("World")

# Output:

# Hello

# World

print("Hello", end=" ")

print("World")

# Output: Hello World

Escape Characters

\n → New line

\t → Tab

\\ → Backslash

\' → Single quote

\" → Double quote

Practice

Print a box of asterisks (4 rows, 19 asterisks each)

Print a hollow box (asterisks on edges, spaces inside)

Print a triangle pattern starting with one asterisk

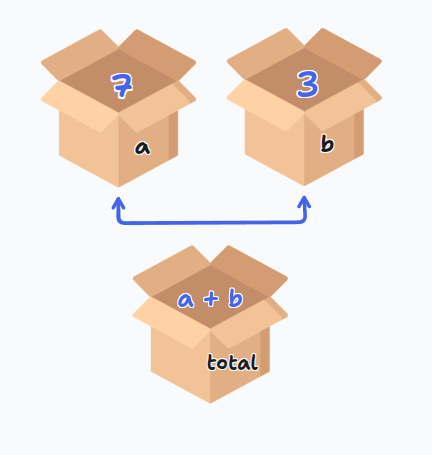

Variables and Assignment

A variable stores a value in memory so you can use it later.

x = 7

y = 3

total = x + y

print(total) # 11

The = sign is for assignment, not mathematical equality. You're telling Python to store the right side value in the left side variable.

Multiple assignment:

x, y, z = 1, 2, 3

Variable Naming Rules

- Must start with letter or underscore

- Can contain letters, numbers, underscores

- Cannot start with number

- Cannot contain spaces

- Cannot use Python keywords (

for,if,class, etc.) - Case sensitive:

age,Age,AGEare different

Assignment Operators

x += 3 → Same as x = x + 3

x -= 2 → Same as x = x - 2

x *= 4 → Same as x = x * 4

x /= 2 → Same as x = x / 2

Reading Input

name = input("What's your name? ")

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

input() always returns a string! Even if the user types 42, you get "42".

Converting input:

age = int(input("How old are you? "))

price = float(input("Enter price: $"))

Practice

Ask for a number, print its square in a complete sentence ending with a period (use sep)

Compute: (512 - 282) / (47 × 48 + 5)

Convert kilograms to pounds (2.2 pounds per kilogram)

Basic Data Types

Strings

Text inside quotes:

name = "Mahmoud"

message = 'Hello'

Can use single or double quotes. Strings can contain letters, numbers, spaces, symbols.

Numbers

- int → Whole numbers:

7,0,-100 - float → Decimals:

3.14,0.5,-2.7

Boolean

True or false values:

print(5 > 3) # True

print(2 == 10) # False

print("a" in "cat") # True

Logical Operators

and → Both must be true

or → At least one must be true

not → Reverses the boolean

== → Equal to

!= → Not equal to

>, <, >=, <= → Comparisons

Practice

Read a DNA sequence and check:

1. Contains BOTH "A" AND "T"

2. Contains "U" OR "T"

3. Is pure RNA (no "T")

4. Is empty or only whitespace

5. Is valid DNA (only A, T, G, C)

6. Contains "A" OR "G" but NOT both

7. Contains any stop codon ("TAA", "TAG", "TGA")

Type Checking and Casting

print(type("hello")) # <class 'str'>

print(type(10)) # <class 'int'>

print(type(3.5)) # <class 'float'>

print(type(True)) # <class 'bool'>

Type casting:

int("10") # 10

float(5) # 5.0

str(3.14) # "3.14"

bool(0) # False

bool(5) # True

list("hi") # ['h', 'i']

int("hello") and float("abc") will cause errors!

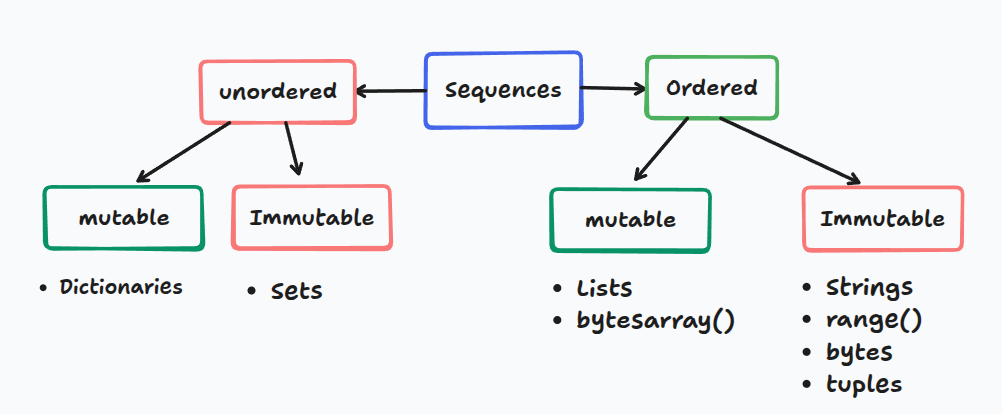

Sequences

Strings

Strings are sequences of characters.

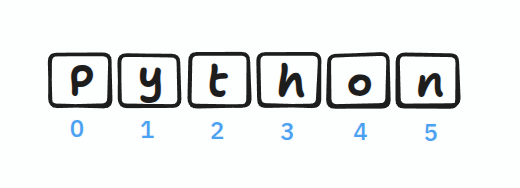

Indexing

Indexes start from 0:

name = "Python"

print(name[0]) # P

print(name[3]) # h

You cannot change characters directly: name[0] = "J" causes an error!

But you can reassign the whole string: name = "Java"

String Operations

# Concatenation

"Hello" + " " + "World" # "Hello World"

# Multiplication

"ha" * 3 # "hahaha"

# Length

len("Python") # 6

# Methods

text = "hello"

text.upper() # "HELLO"

text.replace("h", "j") # "jello"

Common String Methods

.upper(), .lower(), .capitalize(), .title()

.strip(), .lstrip(), .rstrip()

.replace(old, new), .split(sep), .join(list)

.find(sub), .count(sub)

.startswith(), .endswith()

.isalpha(), .isdigit(), .isalnum()

Practice

Convert DNA → RNA only if T exists (don't use if)

Check if DNA starts with "ATG" AND ends with "TAA"

Read text and print the last character

Lists

Lists can contain different types and are mutable (changeable).

numbers = [1, 2, 3]

mixed = [1, "hello", True]

List Operations

# Accessing

colors = ["red", "blue", "green"]

print(colors[1]) # "blue"

# Modifying (lists ARE mutable!)

colors[1] = "yellow"

# Adding

colors.append("black") # Add at end

colors.insert(1, "white") # Add at position

# Removing

del colors[1] # Remove by index

value = colors.pop() # Remove last

colors.remove("red") # Remove by value

# Sorting

numbers = [3, 1, 2]

numbers.sort() # Permanent

sorted(numbers) # Temporary

# Other operations

numbers.reverse() # Reverse in place

len(numbers) # Length

Practice

Print the middle element of a list

Mutate RNA: ["A", "U", "G", "C", "U", "A"]

- Change first "A" to "G"

- Change last "A" to "C"

Swap first and last codon in: ["A","U","G","C","G","A","U","U","G"]

Create complementary DNA: A↔T, G↔C for ["A","T","G","C"]

Slicing

Extract portions of sequences: [start:stop:step]

[0:3] gives indices 0, 1, 2 (NOT 3)

Basic Slicing

numbers = [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9]

numbers[2:5] # [2, 3, 4]

numbers[:3] # [0, 1, 2] - from beginning

numbers[5:] # [5, 6, 7, 8, 9] - to end

numbers[:] # Copy everything

numbers[::2] # [0, 2, 4, 6, 8] - every 2nd element

Negative Indices

Count from the end: -1 is last, -2 is second-to-last

numbers[-1] # 9 - last element

numbers[-3:] # [7, 8, 9] - last 3 elements

numbers[:-2] # [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7] - all except last 2

numbers[::-1] # Reverse!

Practice

Reverse middle 6 elements (indices 2-7) of [0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]

Get every 3rd element backwards from ['a','b',...,'j']

Swap first 3 and last 3 characters in "abcdefghij"

Control Flow

If Statements

age = 18

if age >= 18:

print("Adult")

elif age >= 13:

print("Teen")

else:

print("Child")

elif stops checking after first match. Separate if statements check all conditions.

Practice

Convert cm to inches (2.54 cm/inch). Print "invalid" if negative.

Print student year: ≤23: freshman, 24-53: sophomore, 54-83: junior, ≥84: senior

Number guessing game (1-10)

Loops

For Loops

# Loop through list

for fruit in ["apple", "banana"]:

print(fruit)

# With index

for i, fruit in enumerate(["apple", "banana"]):

print(f"{i}: {fruit}")

# Range

for i in range(5): # 0, 1, 2, 3, 4

print(i)

for i in range(2, 5): # 2, 3, 4

print(i)

for i in range(0, 10, 2): # 0, 2, 4, 6, 8

print(i)

While Loops

count = 0

while count < 5:

print(count)

count += 1

Make sure your condition eventually becomes False!

Control Statements

break → Exit loop immediately

continue → Skip to next iteration

pass → Do nothing (placeholder)

Practice

Print your name 100 times

Print numbers and their squares from 1-20

Print: 8, 11, 14, 17, ..., 89 using a for loop

String & List Exercises

1. Count spaces to estimate words

2. Check if parentheses are balanced

3. Check if word contains vowels

4. Encrypt by rearranging even/odd indices

5. Capitalize first letter of each word

1. Replace all values > 10 with 10

2. Remove duplicates from list

3. Find longest run of zeros

4. Create [1,1,0,1,0,0,1,0,0,0,...]

5. Remove first character from each string

F-Strings (String Formatting)

Modern, clean way to format strings:

name = 'Ahmed'

age = 45

txt = f"My name is {name}, I am {age}"

Number Formatting

pi = 3.14159265359

f'{pi:.2f}' # '3.14' - 2 decimals

f'{10:03d}' # '010' - pad with zeros

f'{12345678:,d}' # '12,345,678' - commas

f'{42:>10d}' # ' 42' - right align

f'{1234.5:>10,.2f}' # ' 1,234.50' - combined

Functions in F-Strings

name = "alice"

f"Hello, {name.upper()}!" # 'Hello, ALICE!'

numbers = [3, 1, 4]

f"Sum: {sum(numbers)}" # 'Sum: 8'

String Methods

split() and join()

# Split

text = "one,two,three"

words = text.split(',') # ['one', 'two', 'three']

text.split() # Split on any whitespace

# Join

words = ['one', 'two', 'three']

', '.join(words) # 'one, two, three'

''.join(['H','e','l','l','o']) # 'Hello'

partition()

Splits at first occurrence:

email = "user@example.com"

username, _, domain = email.partition('@')

# username = 'user', domain = 'example.com'

Character Checks

'123'.isdigit() # True - all digits

'Hello123'.isalnum() # True - letters and numbers

'hello'.isalpha() # True - only letters

'hello'.islower() # True - all lowercase

'HELLO'.isupper() # True - all uppercase

Two Sum Problem

Given an array of integers and a target, return indices of two numbers that add up to target.

# Input: nums = [2, 7, 11, 15], target = 9

# Output: [0, 1] (because 2 + 7 = 9)

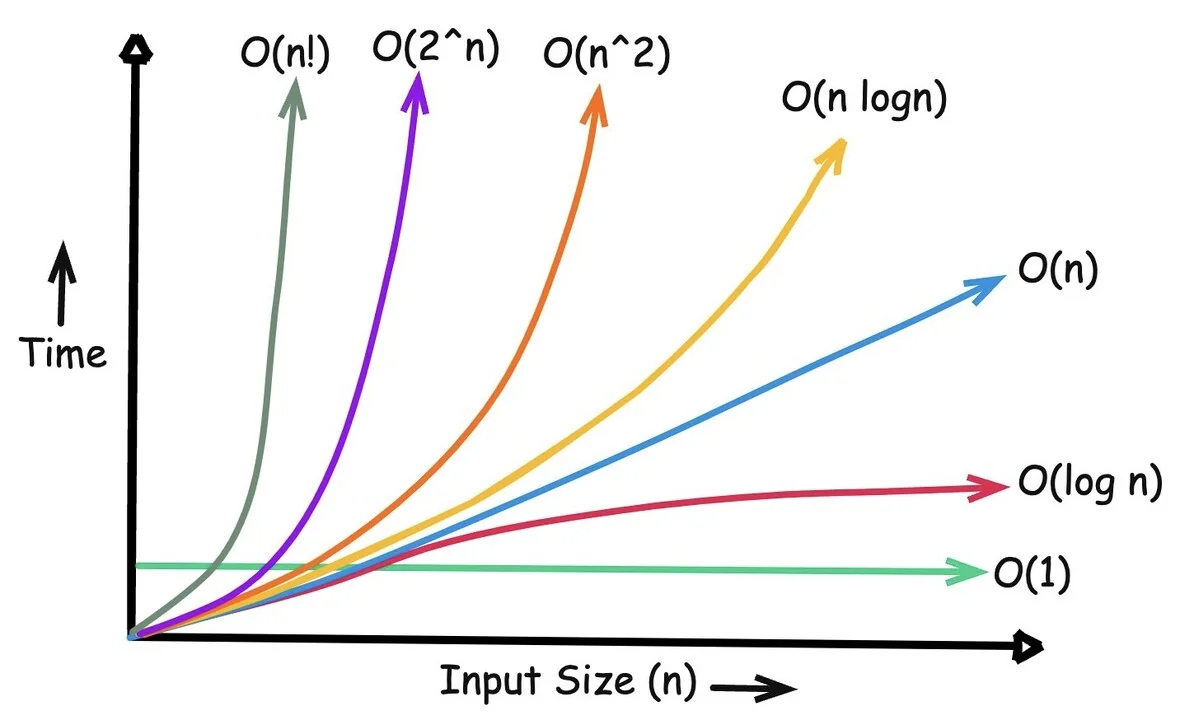

Brute Force Solution (O(n²))

nums = [2, 7, 11, 15]

target = 9

for i in range(len(nums)):

for j in range(i + 1, len(nums)):

if nums[i] + nums[j] == target:

print([i, j])

Time complexity: O(n²)

10 elements = ~100 operations

1,000 elements = ~1,000,000 operations!

Unpacking with * and **

Unpacking Iterables (*)

# Basic unpacking

numbers = [1, 2, 3]

a, b, c = numbers

# Catch remaining items

first, *middle, last = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

# first = 1, middle = [2, 3, 4], last = 5

# In function calls

def add(a, b, c):

return a + b + c

numbers = [1, 2, 3]

add(*numbers) # Same as add(1, 2, 3)

# Combining lists

list1 = [1, 2]

list2 = [3, 4]

combined = [*list1, *list2] # [1, 2, 3, 4]

Unpacking Dictionaries (**)

# Merge dictionaries

defaults = {'color': 'blue', 'size': 'M'}

custom = {'size': 'L'}

final = {**defaults, **custom}

# {'color': 'blue', 'size': 'L'}

# In function calls

def create_user(name, age, city):

print(f"{name}, {age}, {city}")

data = {'name': 'Bob', 'age': 30, 'city': 'NYC'}

create_user(**data)

* unpacks iterables into positional arguments

** unpacks dictionaries into keyword arguments

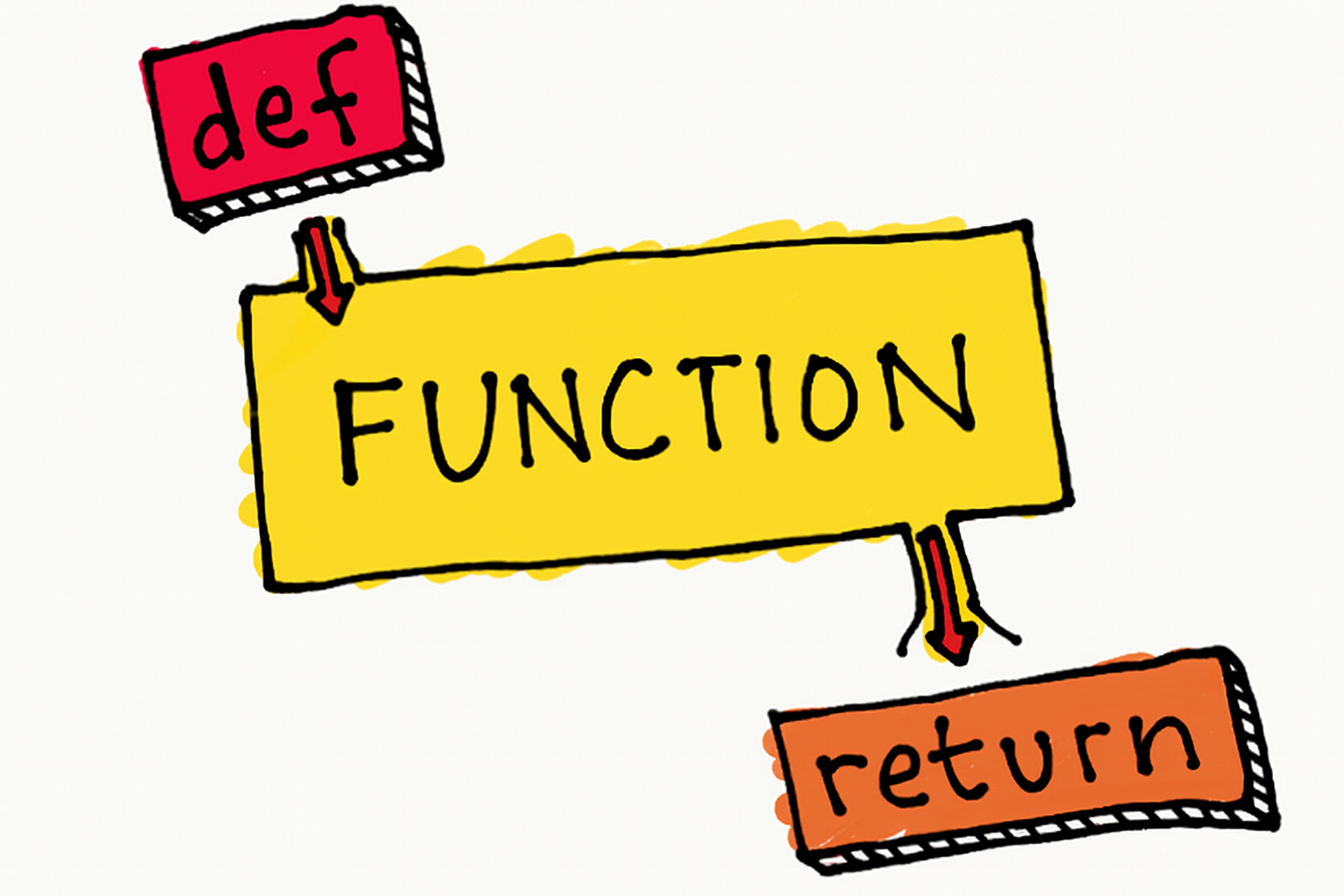

Functions

A function is a reusable block of code that performs a specific task. It's like a recipe you can follow multiple times without rewriting the steps.

The DRY Principle

If you're copying and pasting code, you should probably write a function instead!

Without a function (repetitive):

# Calculating area three times - notice the pattern?

area1 = 10 * 5

print(f"Area 1: {area1}")

area2 = 8 * 6

print(f"Area 2: {area2}")

area3 = 12 * 4

print(f"Area 3: {area3}")

With a function (clean):

def calculate_area(length, width):

return length * width

print(f"Area 1: {calculate_area(10, 5)}")

print(f"Area 2: {calculate_area(8, 6)}")

print(f"Area 3: {calculate_area(12, 4)}")

Basic Function Syntax

Declaring a Function

def greet():

print("Hello, World!")

Anatomy:

def→ keyword to start a functiongreet→ function name (use descriptive names!)()→ parentheses for parameters:→ colon to start the body- Indented code → what the function does

Calling a Function

Defining a function doesn't run it! You must call it.

def greet():

print("Hello, World!")

greet() # Now it runs!

greet() # You can call it multiple times

Parameters and Arguments

Parameters are in the definition. Arguments are the actual values you pass.

def greet(name): # 'name' is a parameter

print(f"Hello, {name}!")

greet("Alice") # "Alice" is an argument

Multiple parameters:

def add_numbers(a, b):

result = a + b

print(f"{a} + {b} = {result}")

add_numbers(5, 3) # Output: 5 + 3 = 8

Return Values

Functions can give back results using return:

def multiply(a, b):

return a * b

result = multiply(4, 5)

print(result) # 20

# Use the result directly in calculations

total = multiply(3, 7) + multiply(2, 4) # 21 + 8 = 29

print() shows output on screen. return sends a value back so you can use it later.

Default Arguments

Give parameters default values if no argument is provided:

def power(base, exponent=2): # exponent defaults to 2

return base ** exponent

print(power(5)) # 25 (5²)

print(power(5, 3)) # 125 (5³)

Multiple defaults:

def create_profile(name, age=18, country="USA"):

print(f"{name}, {age} years old, from {country}")

create_profile("Alice") # Uses both defaults

create_profile("Bob", 25) # Uses country default

create_profile("Charlie", 30, "Canada") # No defaults used

Parameters with defaults must come after parameters without defaults!

# ❌ Wrong

def bad(a=5, b):

pass

# ✅ Correct

def good(b, a=5):

pass

Variable Number of Arguments

*args (Positional Arguments)

Use when you don't know how many arguments will be passed:

def sum_all(*numbers):

total = 0

for num in numbers:

total += num

return total

print(sum_all(1, 2, 3)) # 6

print(sum_all(10, 20, 30, 40)) # 100

**kwargs (Keyword Arguments)

Use for named arguments as a dictionary:

def print_info(**details):

for key, value in details.items():

print(f"{key}: {value}")

print_info(name="Alice", age=25, city="New York")

# Output:

# name: Alice

# age: 25

# city: New York

Combining Everything

When combining, use this order: regular params → *args → default params → **kwargs

def flexible(required, *args, default="default", **kwargs):

print(f"Required: {required}")

print(f"Args: {args}")

print(f"Default: {default}")

print(f"Kwargs: {kwargs}")

flexible("Must have", 1, 2, 3, default="Custom", extra="value")

Scope: Local vs Global

Scope determines where a variable can be accessed in your code.

Local scope: Variables inside functions only exist inside that function

def calculate():

result = 10 * 5 # Local variable

print(result)

calculate() # 50

print(result) # ❌ ERROR! result doesn't exist here

Global scope: Variables outside functions can be accessed anywhere

total = 0 # Global variable

def add_to_total(amount):

global total # Modify the global variable

total += amount

add_to_total(10)

print(total) # 10

Avoid global variables! Pass values as arguments and return results instead.

Better approach:

def add_to_total(current, amount):

return current + amount

total = 0

total = add_to_total(total, 10) # 10

total = add_to_total(total, 5) # 15

Decomposition

Breaking complex problems into smaller, manageable functions. Each function should do one thing well.

Bad (one giant function):

def process_order(items, customer):